I think they should have stuck with the old name; Shangri La promises so much but struggles to deliver it. The little city is flat and a bit dusty. At 3,200 metres high it leaves you short of breath as you walk around. On the first day my legs are wobbly every time I do any exercise at all. And while the old town has its share of attractive old buildings, most house tourist shops and there’s not much soul here.

.jpg) My favourite memories are of the sky: bluer than blue, a bright almost turquoise colour. At night the clouds don’t turn pink, instead they are a burnished gold, sitting like jewels in the bracelet of indigo sky.

My favourite memories are of the sky: bluer than blue, a bright almost turquoise colour. At night the clouds don’t turn pink, instead they are a burnished gold, sitting like jewels in the bracelet of indigo sky. More tourists do now visit the city but some aspects of its development are very un-Shangri La indeed. Perhaps the most disturbing is the Disneyfication of the local monastery.

Zongdian was once home to an important Tibetan Buddhist monastery that was home to more than 800 monks. It had a reputation as a friendly and spiritual place so we decide to visit. (I’m now travelling with Wietse, a young Dutch medical student who I met while trekking on the Tiger Leaping Gorge trek. He’s only 24, which makes me feel suitably ancient, but is gentle, laid back and companionable.) We hook up with Milan and Lise, a Dutch couple and hire cycles for the 6km ride out to the monastery.

The first sign that things have changed is when we’re asked to pay 85yuan, £8.50, entry at a vast hall like complex, manned by soldiers. We cycle on up the hill and the monastery rises up ahead. But it looks very different to the pictures that dot the guide books and town publicity posters.

.jpg) Instead of two temples there are now three; the new central one a work in progress covered by scaffolding and workers. In front of the complex is a huge car park. Three gold tourist buses arrive as we do, disgorging their loads of Chinese tourists complete with guides shouting into megaphones. There is no sense of spirituality as they enter the complex, just a photo op and lots of loud chat.

Instead of two temples there are now three; the new central one a work in progress covered by scaffolding and workers. In front of the complex is a huge car park. Three gold tourist buses arrive as we do, disgorging their loads of Chinese tourists complete with guides shouting into megaphones. There is no sense of spirituality as they enter the complex, just a photo op and lots of loud chat.We let them go then walk up the steps through the small town that surrounds the buildings. The village is quiet. The houses are empty, abandoned, falling into disrepair. The streets are deserted.

In front of the temples are tourist shops and a restaurant, all manned by men in monk’s robes over their jeans and trainers. They lounge about insolently and lack the warmth and gentleness that is integral to Buddhist monks across south east Asia. We feel a little uneasy.

The temples themselves turn out to be brand new. The originals have been knocked down and ‘improved’. Everything is shiny – luridly bright paint has been used to create murals, which are now Chinese rather than Tibetan. There are no monks in sight anywhere. We don’t know where they have gone or why. But it’s clear that this is a not so subtle way to minimise the impact and effect of Tibetan culture in the region and replace it with an acceptable Chinese version.

Subdued we cycle home. That evening we buy a bottle of Tibetan red wine (dry and very drinkable) and reflect on the nature of utopia.

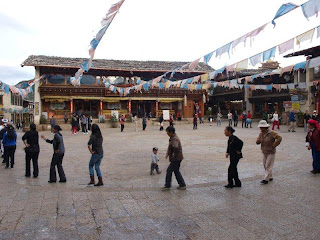

.jpg) Later as we wander out for a meal we find ourselves on the town’s main square. In the centre about 100 people are dancing in a large circle. The music rises and falls, singers chant and call and everyone – grannies, mothers, fathers, teenagers – circle to the tune, arms rising and falling, feet twisting and turning.

Later as we wander out for a meal we find ourselves on the town’s main square. In the centre about 100 people are dancing in a large circle. The music rises and falls, singers chant and call and everyone – grannies, mothers, fathers, teenagers – circle to the tune, arms rising and falling, feet twisting and turning. .jpg) A monk stands smiling on the sideline in his aubergine robes. A toddler wobbles in and out of the circle. And as the music floats around me I finally feel a tiny touch of Shangri La seeping in.

A monk stands smiling on the sideline in his aubergine robes. A toddler wobbles in and out of the circle. And as the music floats around me I finally feel a tiny touch of Shangri La seeping in..jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment